Singapore's Food Challenge

Singapore imports more than 90 percent of our food, necessitating a multi-pronged food security strategy to protect us from disruptions.

On this page

Background

Over 90% of Singapore's food comes from 187 countries and regions. This reliance on food imports leaves us exposed to external forces – from supply shocks in source countries to disruptions in global supply chains.

In response, Singapore has been building and strengthening our food resilience over the years.

History

One of the earliest efforts came about not long after the Japanese occupation, when local food production was primitive, hampered by disease and poor market conditions. In 1959, the Primary Production Department (PPD) was set up to provide for the socio-economic development of rural communities, including raising farming productivity. The measures took off, and by the 1980s, Singapore achieved self-sufficiency with the local production of eggs, poultry, and pork. Over time, however, with the scarcity of land, the number of farms dwindled out and we relied more on imports for our food needs.

In the mid-2000s, the rising volatility in food prices – which eventually gave rise to the global food crisis in 2008 – prompted Singapore to rethink our strategy. Food imports and diversification had to be supplemented by secondary measures, such as stockpiling and local production.

In recent years, Singapore’s food security continues to face increased challenges from climate change, geopolitical developments, and disease outbreaks. Being a net food importer with an open economy, securing global and regional partnerships thus became essential for ensuring stable food flows to Singapore.

Impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on Singapore’s food security

The Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022 demonstrates the ripple effect of disruptions in the global food supply chain. As major exporters of the world’s wheat and corn (25 to 30 per cent and 15 per cent respectively), the halt in exports and trade sanctions from the conflict impacted the global commodity market. To make matters worse, many farms in Ukraine were reportedly destroyed by the war, further jeopardising wheat supplies.

While Singapore does not rely heavily on direct imports from Ukraine or Russia, the ripple effects were felt, especially concerning eggs. The disruption of Russian and Ukrainian grain supplies drove up costs of importing chicken feed. In turn, egg suppliers in Singapore and Malaysia were forced to raise the prices of eggs for consumers.

Today, the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) strengthens Singapore’s food security by adopting a multi-pronged approach to ensure that Singapore has a resilient supply of safe food.

Announced in November 2025, the Singapore Food Story 2 builds on the first iteration of the Singapore Food Story strategy, which was to build up local food production to provide Singapore with a regenerative and assured source of food during supply disruption. Under this new chapter, the original ‘30 by 30’ vision is replaced with new targets for specific food categories.

The 30 by 30 vision

Building up local production was necessary to provide an assured and regenerative source of food during supply disruptions. Hence, the ‘30 by 30’ vision was announced in 2019 by then-Minister for the Environment and Water Resources to produce 30 per cent of our nutritional needs locally by 2030 using less than 1 per cent of land set aside for farming.

Building on our learnings from the ‘30 by 30’ strategy, the refreshed Singapore Food Story 2 is defined by four pillars: (i) diversifying import sources; (ii) growing local; (iii) stockpiling and (iv) global partnerships.

.png)

Overview of the Singapore Food Story 2. Image: Singapore Food Agency (SFA)

Pillar 1: Diversifying import sources

It isn’t until you really watch each part of the supply chain break down that you realise how the whole world is so intricately interconnected.— Ms Lai Su Lyn, former Senior Assistant Director, Supply Chain Resilience Division, MTI

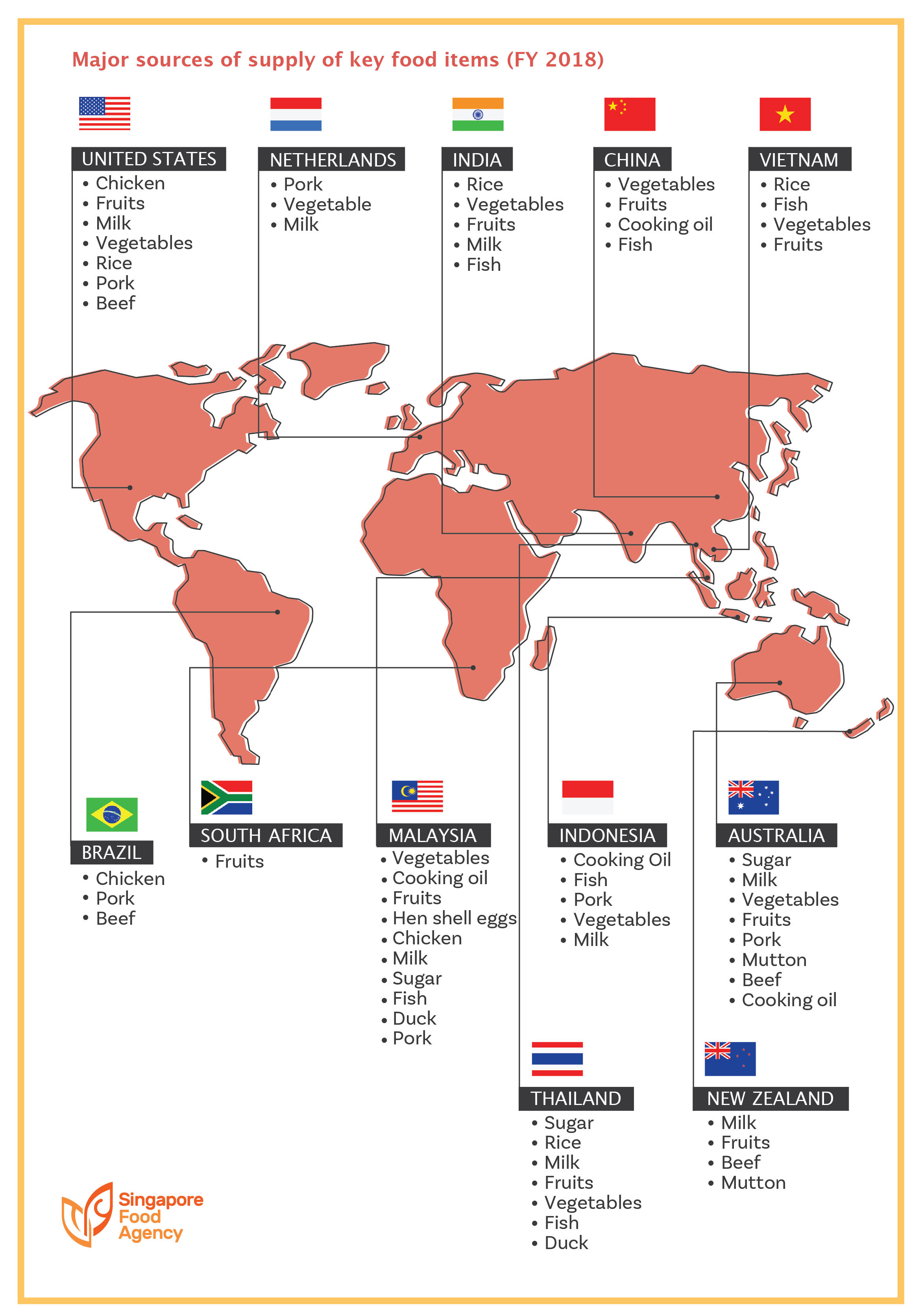

Singapore has been diversifying import sources to minimise the impact of supply disruptions. In 2024, we imported our food from a source network of 187 countries, up from just 140 countries in 2004.

A brief overview of our major sources of key food items (2018). Image: Singapore Food Agency

Having a diversified network of food sources proved to be crucial in tiding us over challenges that came with the COVID-19 pandemic. As countries went into lockdowns or banned certain exports to cater to their domestic needs, SFA tapped its source network. In June 2020, Singapore received the first batch of eggs from Poland. Today, we also import oranges from Egypt, milk powder from Uruguay, and shrimps from Saudi Arabia, as part of efforts to broaden food supplies. This has allowed Singaporeans to enjoy steady access to food supplies despite disruptions from regular suppliers.

Image: Screenshot of Minister Chan Chun Sing's Facebook post, 16 March 2020

Pillar 2: Growing local

Complementing imports with local food production provides us with a buffer supply in the event of overseas supply disruptions, bolstering our food supply resilience.

In 2009, then-Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority of Singapore (AVA) launched the Food Fund, setting aside an initial sum of S$5 million to co-fund research and development in local food farming technology, upgrade local production capabilities, and diversify food sources. The plan was to increase Singapore’s self-sufficiency in eggs, fish, and leafy greens. In 2021, domestic farms met 30, 8 and 4.5 per cent of local needs for these items respectively, indicating progress towards the ‘30 by 30’ vision. Together with other pillars of our food strategy, local production availed us options and flexibility in times of need.

In 2025, it was assessed that local production goals needed to be more targeted and efficient, given our land scarcity. Under the revised targets, local farms will supply 20% of local consumption of fibre, which refers to fresh leafy and fruited vegetables, beansprouts and mushrooms; and 30% of our local consumption of protein, which refers to eggs and seafood.

Technology as a key enabler of growing local

Technology is a key enabler in helping farms do more with less – we invest in agri-tech to make local farms more efficient and productive. For instance, Aquaculture Technologies, Singapore’s first smart floating fish farm. Located off the coast of Pasir Ris, the facility runs on artificial intelligence and video analytics. It expects to produce ten times the minimum yield of a typical coastal fish farm at full capacity.

To help farms manage rising operating expenses, multi-tenanted facilities with common utilities and climate-controlled environments are being explored. These "plug-and-play" spaces can in turn reduce the required start-up capital while enhancing climate resilience.

Beyond producing food at scale, technology can also be harnessed to develop new, alternative, and sustainable food sources. The Agency for Science, Technology and Research’s food and biotechnology institution is working to boost Singapore’s local produce capabilities by developing new, alternative, and sustainable food sources – like crabmeat that come from labs.

Growing food locally remains an important pillar of Singapore’s food security. Yet, demand is a crucial factor for local farms to be commercially viable. For consumers, this means that our choice matters. We can support these local farms by purchasing from them and dining at food businesses that use farm-to-table produce.

.png)

Local produce in Singapore major supermarkets. Image: Singapore Agro-Food Enterprises Federation Limited (SAFEF)

Pillar 3: Stockpiling

To buffer against unforeseen global supply chain disruptions, Singapore stockpiles essential food items in close partnership with private sectors. These food items are typically difficult or impossible to produce locally due to land and resource constraints.

One primary example is rice, a food staple in Singapore. In view of this, the SFA ensures a certain level of in-country stocks of rice through administering the Rice Stockpile Scheme, where rice importers are required to stockpile rice as part of an import licence condition.

Following lessons from global events like COVID-19, the range of stockpiled items has been strategically expanded to include commodities such as frozen protein and canned vegetables.

A stockpile warehouse operated by Singapore supply chain and logistics company YCH Group (22 October 2025). Image: Senior Minister of State Zaqy Mohamad via Facebook.

To strengthen our stockpiling strategy, a new research domain on food resilience was established in 2025. It focuses on climate-induced risk assessment and mitigation systems, and optimised food storage solutions. Through sustained research, Singapore primes itself for the Future Foods industry while advancing safety assessment methods that better protect consumers.

Pillar 4: Global partnerships

In September 2025, outbreaks of avian flu in Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom created a dent in our poultry imports with little warning. Such unforeseen circumstances demonstrate the volatility of our global food supply chains. Exacerbated by an increasingly fragmented global environment, the importance of global partnerships in safeguarding flows of food to Singapore is brought to the fore.

Given this reality, the SFA announced in November 2025 that it will proactively forge partnerships with like-minded countries to add a layer of resilience to existing efforts, ensuring a stable and safe food supply for Singapore.

Examples of global partnerships

The conclusion of the Agreement on Trade in Essential Supplies with New Zealand in October 2025 legally assures that both countries can continue to receive important food items without export prohibitions during disruptions. This is further supported by a Strategic Food Partnership to build resilient agri-food systems, drive food science and innovation, and facilitate agri-food trade.

As a major producer of rice, Vietnam has been and will continue to be a major trading partner. In October 2025, Singapore signed a Memorandum of Cooperation on Rice Trade with Vietnam, which allows Singapore to activate an additional source of rice in times of need.