Thinking Long Term

Urban Planning

A furry head pops up from the water, eyes darting around and checking for danger. It sniffs the air and gives the all-clear to the rest of his troop. One by one, the rest of the otter family pop their heads up, weaving their bodies through the clear waters at Kallang River, drawing delighted squeals from the families walking nearby.

It is not uncommon to spot the family of otters in the Kallang River. But they are not the only reason why Singaporeans often head down to walk by the riverside. For many, taking a walk along the water’s edge helps calm frazzled nerves, while the fresh air provides respite for the ragged urbanite.

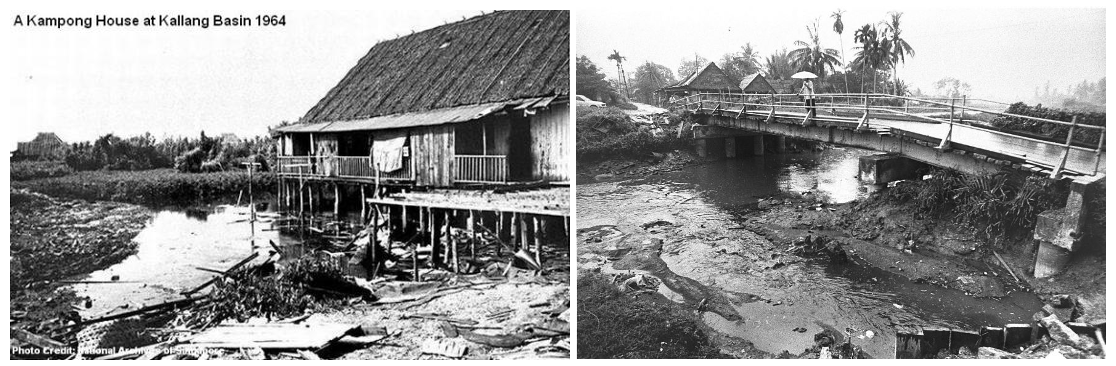

It was not always this case. In the 1970s, the Kallang River was more known for its stench than its sights. The sludge-filled water carried chicken carcasses, rotting fruit and a foul stench that blanketed the area. Similarly, most other waterways in Singapore were also heavily polluted.

Images: Kallang River before the clean-up / NAS

Images: Kallang River before the clean-up / NAS

It took an order by then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew to start a national effort to clean up the waterways around the island. Instead of dead animals, he wanted the rivers and canals to have “more or less clean, translucent water, where fish, water lilies, and other water plants [could] grow, and [for] both sides of the waterway [to] be planted with trees, like willow”. After decades of cleaning, we now have waters so clean that a wide range of animal and plant life thriving in our rivers and waterways.

Image: Kallang River today / Wikipedia Commons and PUB

Image: Kallang River today / Wikipedia Commons and PUB

The transformation of Singapore’s waterways from polluted to pristine is an example of how the Government has made it a priority to ensure that Singapore remains a safe and comfortable home for more than three million Singaporeans.

The transformation did not, however, take place overnight. It took decades of meticulous planning, targeted execution and an ambitious vision. To this end, four factors have enabled Singapore to become an urban oasis.

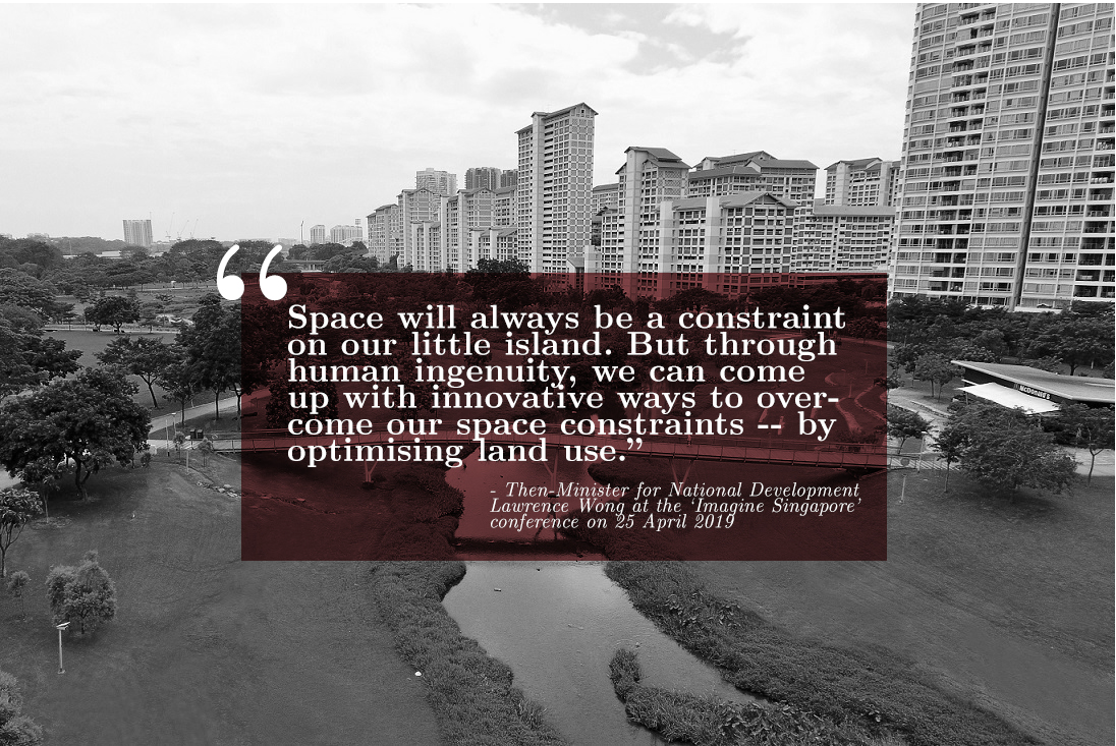

Thinking Long-Term

Singapore’s limited space means that we cannot afford to use our land haphazardly. Our urban planning approach has to optimise the scarce land we have to meet diverse needs, including housing, industries, green areas and recreation.

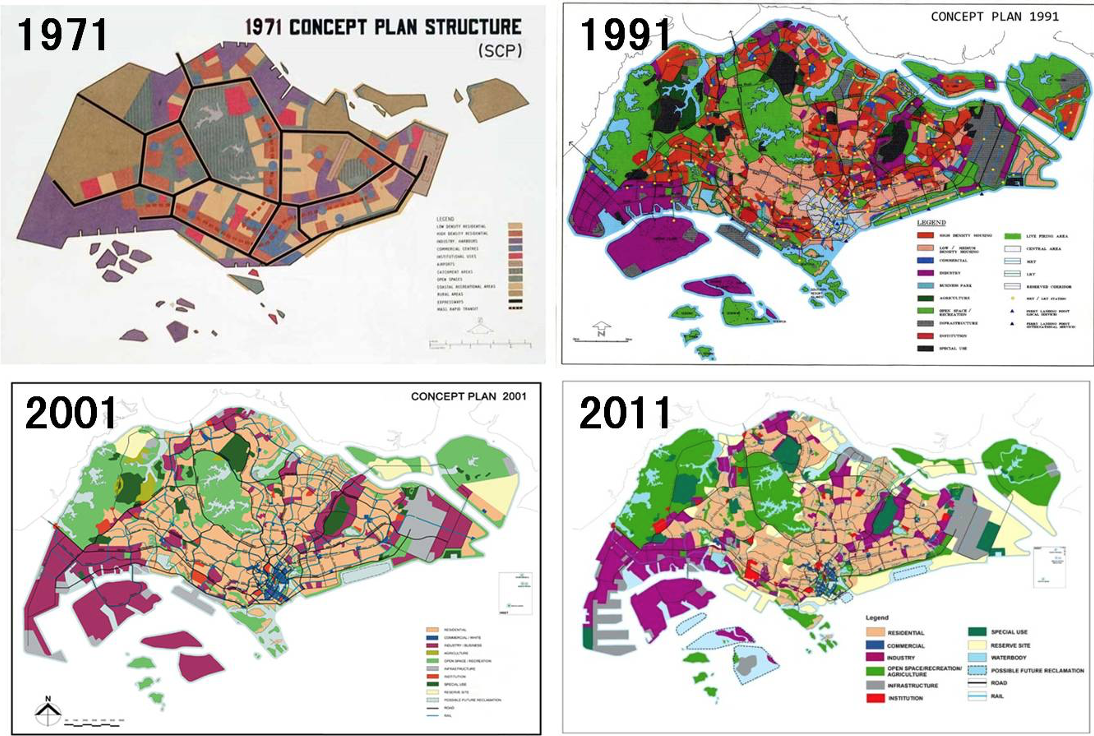

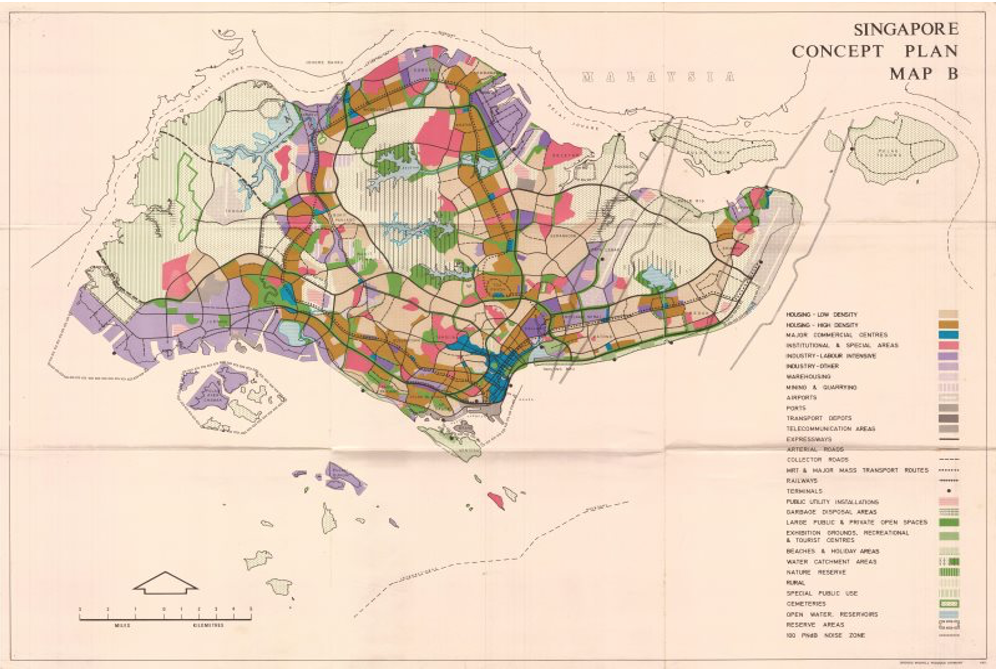

To this end, the Government has taken an integrated and long-term approach to urban planning – the Concept Plan and the Master Plan.

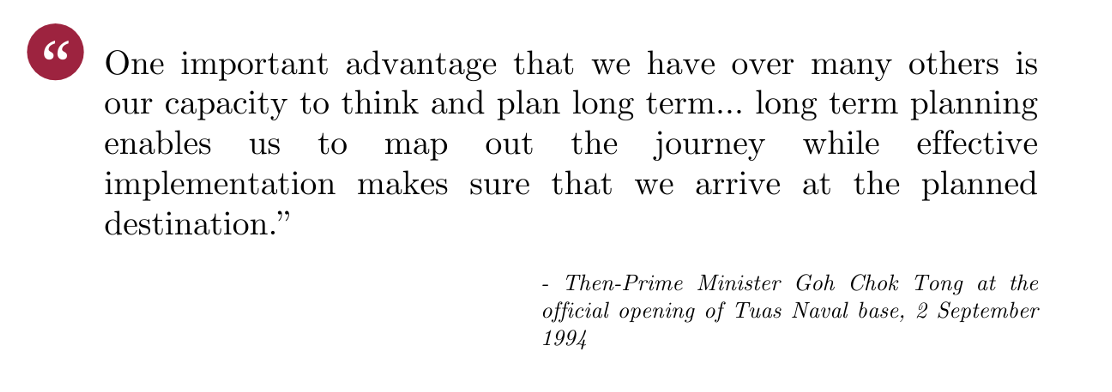

As the strategic land use and transportation plan that provides broad guidelines for Singapore’s physical development over the next 40 to 50 years, the Concept Plan provides the overall strategy. Its goal is to ensure sufficient space to support long-term population growth, economic development, and a good living environment.

Image: Meng, Weiwei & You, Tingting & Duan, Yan & He, Jia. (2021). Planning Practice of Coordinated Development of Urban Traffic and Land Use

Image: Meng, Weiwei & You, Tingting & Duan, Yan & He, Jia. (2021). Planning Practice of Coordinated Development of Urban Traffic and Land Use

Singapore’s first Concept Plan was published in 1971. The plan was a mammoth effort, involving more than 100 local and overseas urban planners, architects, civil servants and academics between 1967 and 1969. It laid the foundations of the land needs for the young nation, setting out the principles for developing housing estates, recreational spaces and industrial estates. Its legacies continue to this day, more than 50 years after the plan was published.

Image: 1971 Concept Plan / URA

Image: 1971 Concept Plan / URA

The Concept Plan set in place critical infrastructures instrumental to Singapore’s economic growth. This included the construction of Changi Airport, which opened in 1981, a Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system, and a network of expressways. The plan also earmarked the Central Area as the Central Business District (CBD).

The second Concept Plan, published in 2001, focused on creating an island city that balanced work, play, culture and commerce. It proposed developing commercial corridors in different parts of the island to bring jobs closer to homes. One of Singapore’s most significant economic engines – Jurong Island – was also borne from this plan.

Example: Jurong Island

Image: Jurong Island / EDB

Image: Jurong Island / EDB

The idea of constructing Jurong Island came about in the 1980s with the plan to establish Singapore as a leading petrochemicals hub.This would reduce the economy’s dependence on electronics manufacturing and strengthen Singapore’s position as a top oil refining centre. But more land was needed to build up the country’s petroleum and petrochemicals industry. The Government subsequently began reclaiming land off Singapore’s southwestern islands.

The plan was to merge seven existing islands (Pulau Merlimau, Pulau Ayer Chawan, Pulau Ayer Merbau, Pulau Seraya, Pulau Sakra, Pulau Pesek, and Pulau Pesek Kecil) into one. The project, built at more than $7 billion, involved massive dredging to triple 10 square km of usable space to 32 square km.

The engineering feat was achieved after meticulous planning. The engineers put together a detailed blueprint to maximise project efficiency and minimise costs. The designers planned shared facilities, centralised logistics, and common corridors.

Reclamation works for Jurong Island began in 1995 – the project was so ambitious that it was initially estimated that the project could be completed only by 2030. But the detailed planning and creative engineering helped speed up the process. The island was fully reclaimed by 2009 – 20 years ahead of schedule.

Jurong Island houses the biggest petrochemicals companies globally in an integrated facility that combines the different parts of the chemicals supply chain. Since the official opening in 2000, Jurong Island has attracted over $50 billion worth of investments.

The latest Concept Plan, published in 2011, looks further into the future, with an eye on providing and sustaining a high-quality living environment for future generations of Singaporeans. The plan sets out parameters for providing affordable homes, enhancing mobility with greater transport connectivity and growing an economy with good jobs.

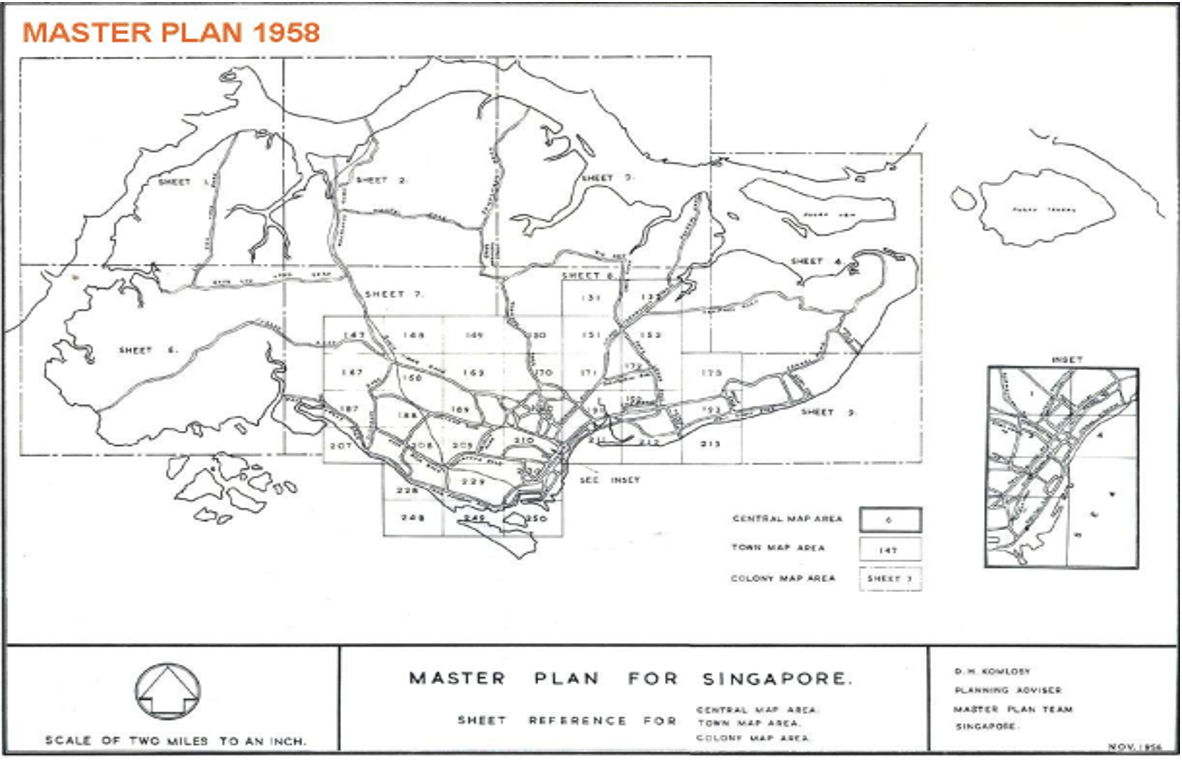

While the Concept Plan takes care of the broad, long-term strategies, the Master Plan goes into detail. It focuses on the medium-term and is reviewed once every five years, guiding Singapore’s development over the next 10 to 15 years. The plan lays out the specifics for individual plots of land.

The latest Concept Plan, published in 2011, looks further into the future, with an eye on providing and sustaining a high-quality living environment for future generations of Singaporeans. The plan sets out parameters for providing affordable homes, enhancing mobility with greater transport connectivity and growing an economy with good jobs.

While the Concept Plan takes care of the broad, long-term strategies, the Master Plan goes into detail. It focuses on the medium-term and is reviewed once every five years, guiding Singapore’s development over the next 10 to 15 years. The plan lays out the specifics for individual plots of land.

Image: 1958 Master Plan / URA

Image: 1958 Master Plan / URA

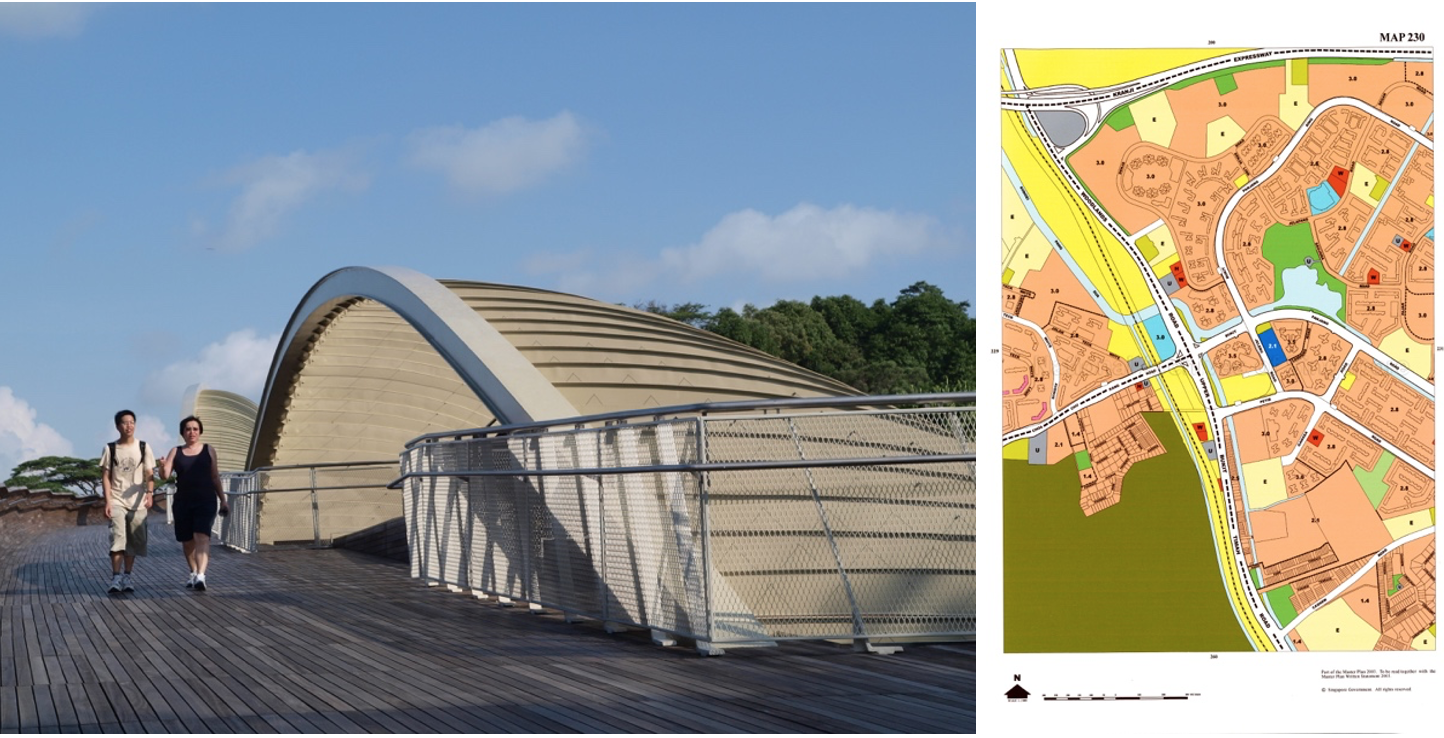

For example, the 2003 Master Plan focused on enhancing and protecting Singapore’s natural and heritage sites. The Southern Ridges – completed in 2008 – is one such example, when the plan first conceived linking various hill parks with the construction of two iconic bridges.

Images: Southern Ridges / NParks and Extract from Master Plan 2003 / NAS

Images: Southern Ridges / NParks and Extract from Master Plan 2003 / NAS

This approach to long-term planning is a crucial reason we can develop our tiny island with an eye on the future. Likewise, our approach to planning was also a key factor that led to our public transport network development. We have had to project into the future – a process that requires us to think beyond our present needs.